Introduction

Young adults have been flocking to the Catholic Church in recent years, prompting many to question why. Charlie Kirk, not too long before he was martyred, answered that question in an interview with Tucker Carlson. Mr. Kirk said: “First of all, they want something that has lasted. They want something that is ancient and that is beautiful, something that has stood the test of time, something that’s not going to change, something that’s all of a sudden not going to all of a sudden just flip around and have some sort of, you know, transgender story hour.” Yes.

Earlier in the same interview, Mr. Carlson railed against baby-boomers, launching his salvo with: “They’re repulsive. They’ve always been repulsive.” From there, boomer identity slid downhill in the wake of his colorful illustration of its self-absorption that supported the conclusion at which he first arrived in boyhood: “I hated them then. I hate them now.” Fair enough.

And yet, as one born into the latter part of the boomer generation in late 1960, destined to grow up in the 1960s and 70s through no fault of my own, I offer not necessarily an excuse but instead an explanation of why at least the later boomers might have drawn the ire of their successors. We had no catechism. And we were raised in the Church in the catechism gap, the repercussions of which, I believe, have been vastly underestimated. I sought to bring light to that dilemma and its repercussions and to encourage a better way forward in the following article.

This article was originally published under the title “In Anticipation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church: The Perspective of One Raised Between the Catechisms” in the Summer 1994 edition of The Living Light: An Interdisciplinary Review of Catholic Religious Education, Catechesis, and Pastoral Ministry an “official publication of the Department of Education of the United States Catholic Conference.” It was later republished in abbreviated form as “Raised Between the Catechisms” in Catholic Digest, September 1994. It appears here, with the permission of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB), in three parts, in the form in which it was submitted for publication in 1993 with some minor editing.

IN ANTICIPATION OF THE CATECHISM OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH: THE PERSPECTIVE OF ONE RAISED BETWEEN THE CATECHISMS

The Living Light, Summer 1994

INTRODUCTION

We stand on the threshold of the third millennium, poised to receive the Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC). Our position in salvation history demands of us a responsible reception of the CCC, because the CCC provides a unique opportunity for renewal in the ongoing conversion of the Church. Indeed, it comes to us through that process of renewal begun at the council of renewal, the Second Vatican Council.

In recognizing the CCC as the catechism of that era, which opened with Pope John XXIII’s 25 January 1959, announcement that he intended to invoke the twenty-first ecumenical council, we must also recognize the catechetical needs of the generation raised within that era without benefit of its catechism. As one of that generation, I offer some reflections on my own catechetical experience and some conclusions I have drawn from it.

In a few short years a generation of little children stepped across that epochal line between the old and the new, unaware of their place in salvation history and the implications it would have in their lives.

CATECHESIS IN PERSPECTIVE

I had a rare opportunity to publicly articulate and clarify some of my concerns about the catechetical experience of my generation at a gathering of catechetical leaders of the Diocese of ______ in the fall of 1992. Richard Reichert, Consultant for Adult Education and Human Sexuality for the Diocese of Green Bay, gave a thoughtful presentation on the reactionary mode of the Church after the splintering of Protestant denominations and the Council of Trent in the 16th century, and the consequent reactionary catechesis of that period, a catechesis that concentrated on defining the Catholic Church in opposition to those Protestant denominations. Mr. Reichert contended that the Second Vatican Council finally brought to an end the Tridentine era and its catechism as one of the few, if not the only, ecumenical councils to be called not in reaction to a heresy, but rather as a means of renewal.

As I listened, I realized that we were still talking about the catechetical experience of Mr. Reichert and his contemporaries, which comprised the large majority of those assembled. But the period being discussed had passed over thirty years ago. What about the Vatican II generation, those of us whose catechetical experience began after the start of the Second Vatican Council?

In order to address the serious catechetical needs of those in their mid-thirties and younger, catechetical leaders must shift their focus from the catechetical experience of those who made the transition from pre-Vatican II to Vatican II to the catechetical experience of those of us who grew up in the Vatican II era. Though the transition was not without its difficulties, even trauma for some, it is time to let go and move beyond that period to address the dire catechetical needs of that generation raised within the trauma, unaware of their ecclesiological and catechetical context.

When Mr. Reichert invited us to comment, I pointed out that while it is true that Vatican II was not called in reaction to a heresy, still the catechesis that developed around it was a reactionary catechesis to the catechesis in place before Vatican II. I said that I was born in 1960 and graduated from high school in 1979 (the year of publication of Sharing the Light of Faith: National Catechetical Directory for Catholics of the United States). I literally grew up in the 60’s and 70’s, and I remember nothing from my religious education classes except playing volleyball, having rap sessions and deciding whom we would kick out of a fallout shelter if the bomb dropped, all of which I could have done without religious education.

“He is absolutely right. I was a part of that. We painted rocks for class.”

I do not remember learning much about the Church, its history, structure, magisterium, and Scriptures, and I wanted to know. I do not remember ever seeing anything resembling a textbook in high-school religious education. I wanted to know how we got from Jesus to the Church of the twentieth century, what were the differences between the Protestants and us, why there were different Christian denominations, what made sacraments so special and from where sacred Scripture had come, among other things. I knew my own personal theology, in which evolution figured prominently, but had no way of knowing that it was consistent with Catholic teaching, and misrepresentations of Catholic teaching by non-Catholics and the press did not help matters any. I do not remember ever hearing of Vatican II, let alone knowing what it was, until I went to college. And, again, I wanted to know. I finally decided to study theology at the graduate level, with no other motivation than personal enrichment, to learn basic information about the Catholic Church and its story.

Certainly, parents were responsible as primary educators, and I know that I learned a good deal more at home about Catholicism than did most of my contemporaries [thus, all of my siblings are still practicing Catholics with no divorces]. Still, I think even parents assumed that we were learning more than we were at Catholic school and religious education, because they assumed a systematic religious education similar to the one through which they had learned. But things were changing drastically.

Ours is the generation that arrived at school one day to find Sister in a new, abbreviated habit. On another day we learned that the school would no longer attend daily Mass. My sister, one year ahead of me, learned to confess her sins according to species and number. I cannot remember hearing of such a thing until my sister told me about it well after I had participated in the Sacrament of Reconciliation a number of times. My second grade class was the last one at our parish to march two by two into the church, girls in white dresses and veils, boys in white shirts and dark ties, to receive our First Holy Communion as a class. My brother, one year behind me, and our younger siblings received their First Eucharist at home Masses. In a few short years a generation of little children stepped across that epochal line between the old and the new, unaware of their place in salvation history and the implications it would have in their lives.

Our parochial school was not staffed primarily by the sisters as in days gone by. In eight years of parochial school only two of my teachers were sisters. Still, almost all of the teachers in our school were excellent, but many were young without much background in religious education. At the same time, even the more experienced teachers were expected to adjust to religious education materials that concentrated more and more on personal experience, self esteem, relationships, and less and less on religion.

We must face the fact that my generation is almost wholly ignorant of the catechism that helped mold the majority of Catholics who directed our catechesis.

Amidst all this, Catholics were unsure about what they could teach and with what vocabulary they could teach it, as self-styled progressives denigrated much of pre-Vatican II catechetical content, method, and terminology. Most Catholic parents and teachers probably wanted to support Vatican II initiatives, and they themselves struggled with the changes it brought to their own experience of the Church, but unlike our parents and teachers, those of us growing up in the period did not have the pre-Vatican II experience from which to put it all in perspective.

As I expressed a condensed version of the above, Mr. Reichert nodded his head, and when I finished he addressed the others present, “Ladies and gentlemen, this young man’s catechetical experience is the experience of most of the parents of children in our religious education programs. What does that tell you about where we have a lot of work to do?” And those gathered answered with him, “The parents.”

Mr. Reichert continued, “He is absolutely right. I was a part of that. We painted rocks for class.” He admitted that that was the mood of the times and that catechesis suffered for it.

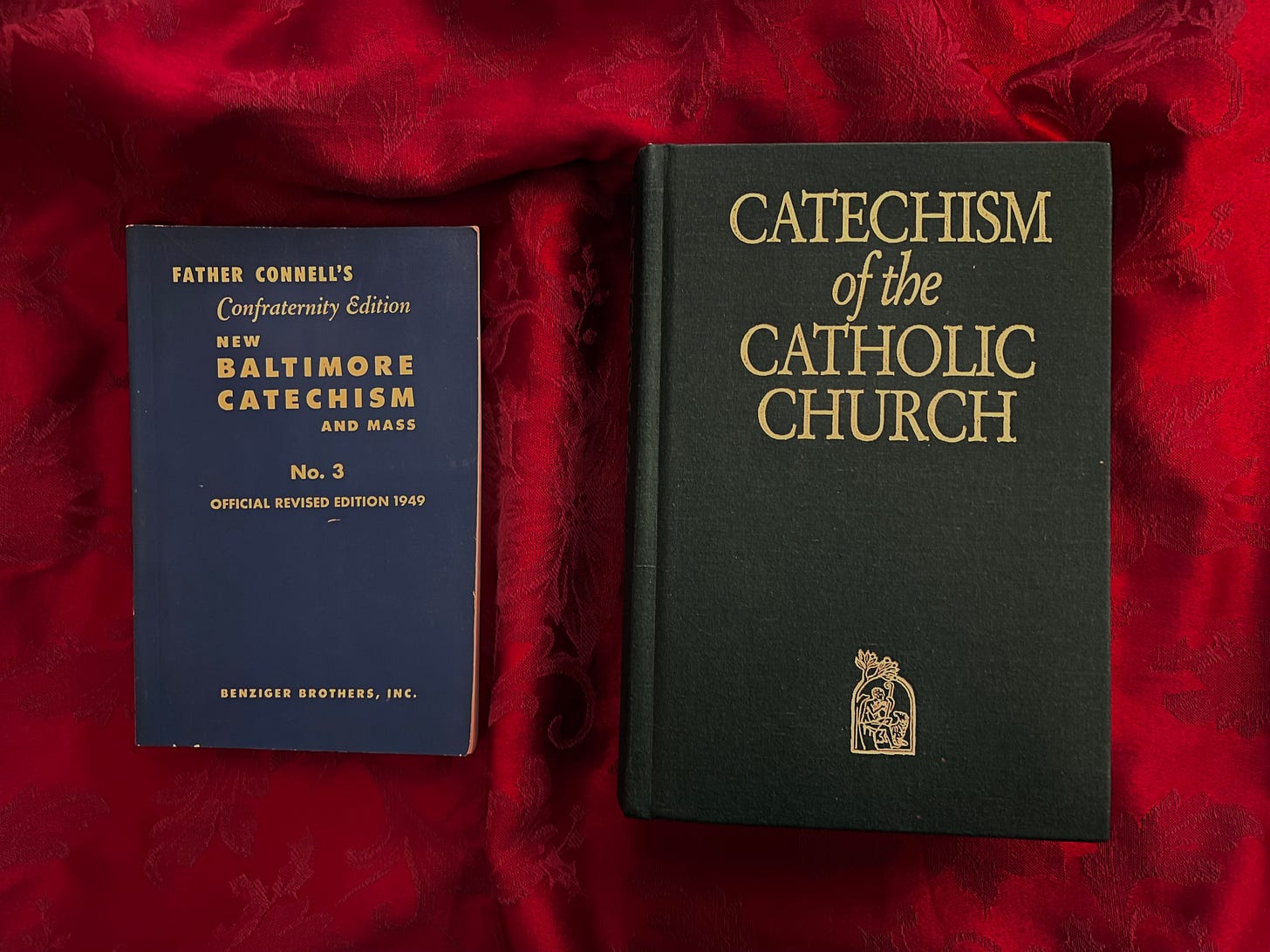

Further elucidation of this situation might be gleaned from a comment made by Matt Hayes, a member of the United States Catholic Conference’s Ad Hoc Committee on the Implementation of the Catechism. At a recent workshop on the CCC given in the Diocese of _______, Mr. Hayes admitted that many are anticipating the CCC with skepticism because, though it will be a major catechism, the catechetical context for its reception is a minor catechism, namely the Baltimore Catechism (1885), derived from the last major catechism of the universal church, the so-called Roman Catechism of 1566.

And this demands that we stop apologizing for Catholic teaching that was commissioned by Jesus and handed on through the apostles and their successors.

Some may argue that this view ignores such catechetical documents as the General Catechetical Directory (1971), Sharing the Light of Faith: National Catechetical Directory for Catholics of the United States (1979), and the Apostolic Exhortation on Catechetics (Catechesi Tradendae) (1979). I would disagree. I believe that though these are important documents, they are virtually unknown to most Catholics in the pew, and even to many of those charged with directing catechetical programs. Furthermore, unlike these documents, the Baltimore Catechism was a catechism, in a form accessible to the Catholic in the pew, so widely distributed and implemented over such a long period of time that its use and eventual removal affected the catechetical experience of the Church of the United States in a unique and lasting way. Accordingly, the Baltimore Catechism can be properly said to be the catechetical context for the reception of the CCC by the Church in the United States.

If then the Baltimore Catechism is the catechetical context for the reception of the CCC, then for many it is a context of ignorance. Like most of my contemporaries, I have never seen the Baltimore Catechism (except possibly some snippets of it, as of some relic, in a graduate ecclesiology course). This is notwithstanding the fact that I am thirty-three years old and have attended Catholic elementary school and junior high, religious education in high school, a Jesuit college and graduate school in theology.

As a director of religious education, I am fully aware that many catechetical leaders, who dismiss with a shudder the Baltimore Catechism as one might dismiss a period of imprisonment, not without torture, would consider this ignorance of it to be a true sign of the great strides made in religious education since the Second Vatican Council. I leave it to theologians to debate the merit of that point of view. Whether or not the Baltimore Catechism should have been used in our education is not as relevant or important as the blunt fact that it was not. We must face the fact that my generation is almost wholly ignorant of the catechism that helped mold the majority of Catholics who directed our catechesis.

Thus, it is time to realize that if the Baltimore Catechism is the practical context for the reception of the CCC, then the vast majority of Catholics in the United States in their mid-thirties and younger have little or no knowledge of the Catholic Church, its foundation, its history, its Scriptures, its theologies, its sacraments, its hierarchy, its magisterium, its relationship to Protestant denominations, its relevance in their lives. They have never heard of the Baltimore Catechism. Consequently, it is time to stop reacting to the Baltimore Catechism and the methods used to teach from it, and it is time to offer a substantial religious education that puts demands for learning on those who are instructed by it, just as the Christian life puts demands for living on those who are called to it. And this demands that we stop apologizing for Catholic teaching that was commissioned by Jesus and handed on through the apostles and their successors. The Church is not perfect, given the sinfulness of its members, but it was founded and commissioned by Jesus (Matthew 16:18-19; 18:18; 28:18-20) and has a profound theological and magisterial tradition, and that needs no apology.

Part Two to follow shortly.

Please like, share, comment, or subscribe as you feel inclined.

Thank you,

P. A. Ritzer